History Of Agriculture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Early people began altering communities of

Early people began altering communities of  Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe and included a diverse range of taxa. At least 11 separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent

Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe and included a diverse range of taxa. At least 11 separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent  It was not until after 9500 BC that the eight so-called founder crops of agriculture appear: first

It was not until after 9500 BC that the eight so-called founder crops of agriculture appear: first  In northern

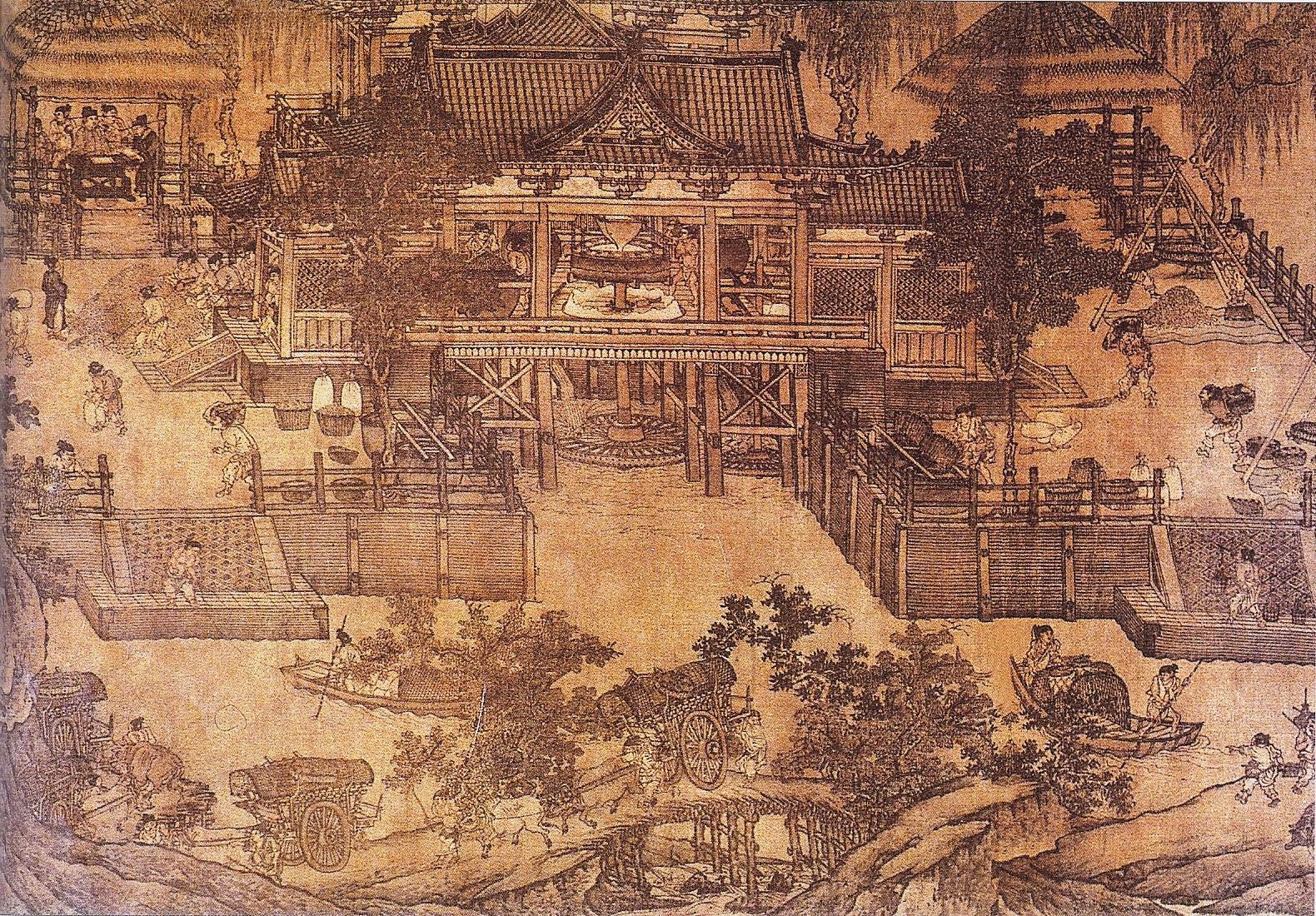

In northern  In southern China, rice was domesticated in the

In southern China, rice was domesticated in the

The civilization of Ancient Egypt was indebted to the

The civilization of Ancient Egypt was indebted to the

Records from the

Records from the  For agricultural purposes, the Chinese had innovated the

For agricultural purposes, the Chinese had innovated the

In the Greco-Roman world of Classical antiquity, Roman agriculture was built on techniques originally pioneered by the Sumerians, transmitted to them by subsequent cultures, with a specific emphasis on the cultivation of crops for trade and export. Ancient Rome, The Romans laid the groundwork for the

In the Greco-Roman world of Classical antiquity, Roman agriculture was built on techniques originally pioneered by the Sumerians, transmitted to them by subsequent cultures, with a specific emphasis on the cultivation of crops for trade and export. Ancient Rome, The Romans laid the groundwork for the

The earliest known areas of possible agriculture in the Americas dating to about 9000 BC are in Colombia, near present-day Pereira, Colombia, Pereira, and by the Las Vegas culture (archaeology), Las Vegas culture in Ecuador on the Santa Elena Province, Santa Elena peninsula. The plants cultivated (or manipulated by humans) were Goeppertia allouia, leren (''Calathea allouia''), Maranta arundinacea, arrowroot (''Maranta arundinacea''),

The earliest known areas of possible agriculture in the Americas dating to about 9000 BC are in Colombia, near present-day Pereira, Colombia, Pereira, and by the Las Vegas culture (archaeology), Las Vegas culture in Ecuador on the Santa Elena Province, Santa Elena peninsula. The plants cultivated (or manipulated by humans) were Goeppertia allouia, leren (''Calathea allouia''), Maranta arundinacea, arrowroot (''Maranta arundinacea''),

In Mesoamerica, wild

In Mesoamerica, wild

The indigenous people of the Eastern Agricultural Complex, Eastern U.S. domesticated numerous crops. Sunflowers, tobacco, varieties of squash and ''Chenopodium'', as well as crops no longer grown, including Iva annua, marsh elder and Hordeum pusillum, little barley. Wild foods including wild rice and maple sugar were harvested. The domesticated strawberry is a hybrid of a Chilean and a North American species, developed by breeding in Europe and North America. Two major crops, pecans and Concord grapes, were used extensively in prehistoric times but do not appear to have been domesticated until the 19th century.

The Agriculture in the prehistoric Southwest, indigenous people in what is now California and the Pacific Northwest practiced various forms of

The indigenous people of the Eastern Agricultural Complex, Eastern U.S. domesticated numerous crops. Sunflowers, tobacco, varieties of squash and ''Chenopodium'', as well as crops no longer grown, including Iva annua, marsh elder and Hordeum pusillum, little barley. Wild foods including wild rice and maple sugar were harvested. The domesticated strawberry is a hybrid of a Chilean and a North American species, developed by breeding in Europe and North America. Two major crops, pecans and Concord grapes, were used extensively in prehistoric times but do not appear to have been domesticated until the 19th century.

The Agriculture in the prehistoric Southwest, indigenous people in what is now California and the Pacific Northwest practiced various forms of

Indigenous Australians were predominately nomadic hunter-gatherers. Due to the policy of ''terra nullius'', Aboriginals were regarded as not having been capable of sustained agriculture. However, the current consensus is that various agricultural methods were employed by the indigenous people.

In two regions of Central Australia, the central west coast and eastern central Australia, forms of agriculture were practiced. People living in permanent settlements of over 200 residents sowed or planted on a large scale and stored the harvested food. The Nhanda and Amangu of the central west coast grew yams (''Dioscorea, Dioscorea hastifolia''), while various groups in eastern central Australia (the Corners Region) planted and harvested bush onions (''yaua'' – ''Cyperus bulbosus''), native millet (''cooly, tindil'' – ''Panicum decompositum'') and a Sporocarp (ferns), sporocarp, ''ngardu'' (''Marsilea drummondii'').

Indigenous Australians used systematic burning, fire-stick farming, to enhance natural productivity. In the 1970s and 1980s archaeological research in south west Victoria established that the Gunditjmara and other groups had developed sophisticated eel farming and fish trapping systems over a period of nearly 5,000 years. The archaeologist Harry Lourandos suggested in the 1980s that there was evidence of 'intensification' in progress across Australia, a process that appeared to have continued through the preceding 5,000 years. These concepts led the historian Bill Gammage to argue that in effect the whole continent was a managed landscape.

Torres Strait Islanders are now known to have planted

Indigenous Australians were predominately nomadic hunter-gatherers. Due to the policy of ''terra nullius'', Aboriginals were regarded as not having been capable of sustained agriculture. However, the current consensus is that various agricultural methods were employed by the indigenous people.

In two regions of Central Australia, the central west coast and eastern central Australia, forms of agriculture were practiced. People living in permanent settlements of over 200 residents sowed or planted on a large scale and stored the harvested food. The Nhanda and Amangu of the central west coast grew yams (''Dioscorea, Dioscorea hastifolia''), while various groups in eastern central Australia (the Corners Region) planted and harvested bush onions (''yaua'' – ''Cyperus bulbosus''), native millet (''cooly, tindil'' – ''Panicum decompositum'') and a Sporocarp (ferns), sporocarp, ''ngardu'' (''Marsilea drummondii'').

Indigenous Australians used systematic burning, fire-stick farming, to enhance natural productivity. In the 1970s and 1980s archaeological research in south west Victoria established that the Gunditjmara and other groups had developed sophisticated eel farming and fish trapping systems over a period of nearly 5,000 years. The archaeologist Harry Lourandos suggested in the 1980s that there was evidence of 'intensification' in progress across Australia, a process that appeared to have continued through the preceding 5,000 years. These concepts led the historian Bill Gammage to argue that in effect the whole continent was a managed landscape.

Torres Strait Islanders are now known to have planted

By AD 900, developments in smelting, iron smelting allowed for increased production in Europe, leading to developments in the production of agricultural implements such as

By AD 900, developments in smelting, iron smelting allowed for increased production in Europe, leading to developments in the production of agricultural implements such as

Maize and cassava were introduced from Brazil into Africa by Portuguese traders in the 16th century, becoming staple foods, replacing native African crops. After its introduction from South America to Spain in the late 1500s, the potato became a staple crop throughout Europe by the late 1700s. The potato allowed farmers to produce more food, and initially added variety to the European diet. The increased supply of food reduced disease, increased births and reduced mortality, causing a population boom throughout the British Empire, the US and Europe. The introduction of the potato also brought about the first intensive use of fertilizer, in the form of guano imported to Europe from Peru, and the first artificial pesticide, in the form of an arsenic compound used to fight Colorado potato beetles. Before the adoption of the potato as a major crop, the dependence on grain had caused repetitive regional and national famines when the crops failed, including 17 major famines in England between 1523 and 1623. The resulting dependence on the potato however caused the European Potato Failure, a disastrous crop failure from potato blight, disease that resulted in widespread Great Famine (Ireland), famine and the death of over one million people in Ireland alone. Adapted from ''1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created'', by Charles C. Mann.

Maize and cassava were introduced from Brazil into Africa by Portuguese traders in the 16th century, becoming staple foods, replacing native African crops. After its introduction from South America to Spain in the late 1500s, the potato became a staple crop throughout Europe by the late 1700s. The potato allowed farmers to produce more food, and initially added variety to the European diet. The increased supply of food reduced disease, increased births and reduced mortality, causing a population boom throughout the British Empire, the US and Europe. The introduction of the potato also brought about the first intensive use of fertilizer, in the form of guano imported to Europe from Peru, and the first artificial pesticide, in the form of an arsenic compound used to fight Colorado potato beetles. Before the adoption of the potato as a major crop, the dependence on grain had caused repetitive regional and national famines when the crops failed, including 17 major famines in England between 1523 and 1623. The resulting dependence on the potato however caused the European Potato Failure, a disastrous crop failure from potato blight, disease that resulted in widespread Great Famine (Ireland), famine and the death of over one million people in Ireland alone. Adapted from ''1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created'', by Charles C. Mann.

Advice on more productive techniques for farming began to appear in England in the mid-17th century, from writers such as Samuel Hartlib, Walter Blith and others. The main problem in sustaining agriculture in one place for a long time was the depletion of nutrients, most importantly nitrogen levels, in the soil. To allow the soil to regenerate, productive land was often let fallow and in some places

Advice on more productive techniques for farming began to appear in England in the mid-17th century, from writers such as Samuel Hartlib, Walter Blith and others. The main problem in sustaining agriculture in one place for a long time was the depletion of nutrients, most importantly nitrogen levels, in the soil. To allow the soil to regenerate, productive land was often let fallow and in some places

Dan Albone constructed the first commercially successful gasoline-powered general purpose tractor in 1901, and the 1923 International Harvester Farmall tractor marked a major point in the replacement of draft animals (particularly horses) with machines. Since that time, self-propelled mechanical harvesters (combine harvester, combines), Planter (farm implement), planters, transplanters and other equipment have been developed, further revolutionizing agriculture. These inventions allowed farming tasks to be done with a speed and on a scale previously impossible, leading modern farms to output much greater volumes of high-quality produce per land unit.

Dan Albone constructed the first commercially successful gasoline-powered general purpose tractor in 1901, and the 1923 International Harvester Farmall tractor marked a major point in the replacement of draft animals (particularly horses) with machines. Since that time, self-propelled mechanical harvesters (combine harvester, combines), Planter (farm implement), planters, transplanters and other equipment have been developed, further revolutionizing agriculture. These inventions allowed farming tasks to be done with a speed and on a scale previously impossible, leading modern farms to output much greater volumes of high-quality produce per land unit.

The Haber process, Haber-Bosch method for synthesizing

The Haber process, Haber-Bosch method for synthesizing

The Green Revolution was a series of research, development, and technology transfer initiatives, between the 1940s and the late 1970s. It increased agriculture production around the world, especially from the late 1960s. The initiatives, led by Norman Borlaug and credited with saving over a billion people from starvation, involved the development of high-yielding varieties of cereal grains, expansion of irrigation infrastructure, modernization of management techniques, distribution of hybridized seeds, synthetic fertilizers, and

The Green Revolution was a series of research, development, and technology transfer initiatives, between the 1940s and the late 1970s. It increased agriculture production around the world, especially from the late 1960s. The initiatives, led by Norman Borlaug and credited with saving over a billion people from starvation, involved the development of high-yielding varieties of cereal grains, expansion of irrigation infrastructure, modernization of management techniques, distribution of hybridized seeds, synthetic fertilizers, and

excerpt

* Federico, Giovanni. ''Feeding the World: An Economic History of Agriculture 1800–2000'' (Princeton UP, 2005) highly quantitative * Grew, Raymond

''Food in Global History''

(1999) * Heiser, Charles B. ''Seed to Civilization: The Story of Food'' (W.H. Freeman, 1990) * Herr, Richard, ed. ''Themes in Rural History of the Western World'' (Iowa State UP, 1993) * Mazoyer, Marcel, and Laurence Roudart. ''A History of World Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis'' (Monthly Review Press, 2006) Marxist perspective * Prentice, E. Parmalee

''Hunger and History: The Influence of Hunger on Human History''

(Harper, 1939) * Tauger, Mark. ''Agriculture in World History'' (Routledge, 2008)

The economic history of china: with special reference to agriculture

' (Columbia University, 1921) * Murray, Jacqueline. ''The First European Agriculture'' (Edinburgh UP, 1970) * Oka, H-I. ''Origin of Cultivated Rice'' (Elsevier, 2012) * Price, T.D. and A. Gebauer, eds. ''Last Hunters – First Farmers: New Perspectives on the Prehistoric Transition to Agriculture'' (1995) * Srivastava, Vinod Chandra, ed. ''History of Agriculture in India'' (5 vols., 2014). From 2000 BC to present. * Stevens, C.E. "Agriculture and Rural Life in the Later Roman Empire" in ''Cambridge Economic History of Europe, Vol. I, The Agrarian Life of the Middle Ages'' (Cambridge UP, 1971) * * Yasuda, Y., ed. ''The Origins of Pottery and Agriculture'' (SAB, 2003)

in JSTOR

in Britain, 1750–1850 * Ludden, David, ed.

New Cambridge History of India: An Agrarian History of South Asia

' (Cambridge, 1999). * * Mintz, Sidney. ''Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History'' (Penguin, 1986) * Reader, John. ''Propitious Esculent: The Potato in World History'' (Heinemann, 2008) a standard scholarly history * Salaman, Redcliffe N. ''The History and Social Influence of the Potato'' (Cambridge, 2010)

A history of agriculture in Europe and America

' (Crofts, 1925) * Harvey, Nigel. ''The Industrial Archaeology of Farming in England and Wales'' (HarperCollins, 1980) * Hoffman, Philip T. ''Growth in a Traditional Society: The French Countryside, 1450–1815'' (Princeton UP, 1996) * Hoyle, Richard W., ed. ''The Farmer in England, 1650–1980'' (Routledge, 2013

online review

* Kussmaul, Ann. ''A General View of the Rural Economy of England, 1538–1840'' (Cambridge University Press, 1990) * Langdon, John. ''Horses, Oxen and Technological Innovation: The Use of Draught Animals in English Farming from 1066 to 1500'' (Cambridge UP, 1986) * * Moon, David. ''The Plough that Broke the Steppes: Agriculture and Environment on Russia's Grasslands, 1700–1914'' (Oxford UP, 2014) * Slicher van Bath, B.H. ''The Agrarian History of Western Europe, AD 500–1850'' (Edward Arnold, reprint, 1963) * Thirsk, Joan, et al. ''The Agrarian History of England and Wales'' (Cambridge University Press, 8 vols., 1978) * Williamson, Tom. ''Transformation of Rural England: Farming and the Landscape 1700–1870'' (Liverpool UP, 2002) * Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina, Rachel Duffett, and Alain Drouard, eds. ''Food and war in twentieth century Europe'' (Ashgate, 2011)

A History of Agriculture in Europe and America

'' (F.S. Crofts, 1925) * Gray, L.C. ''History of Agriculture in the Southern United States to 1860'' (P. Smith, 1933

Volume I onlineVolume 2

* Hart, John Fraser. ''The Changing Scale of American Agriculture''. (University of Virginia Press, 2004) * Hurt, R. Douglas. ''American Agriculture: A Brief History'' (Purdue UP, 2002) * * O'Sullivan, Robin. ''American Organic: A Cultural History of Farming, Gardening, Shopping, and Eating'' (University Press of Kansas, 2015) * Rasmussen, Wayne D., ed. ''Readings in the history of American agriculture'' (University of Illinois Press, 1960) * Robert, Joseph C.

The story of tobacco in America

' (University of North Carolina Press, 1949) * Russell, Howard. ''A Long Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of Farming In New England'' (UP of New England, 1981) * Russell, Peter A. ''How Agriculture Made Canada: Farming in the Nineteenth Century'' (McGill-Queen's UP, 2012) * Schafer, Joseph.

The social history of American agriculture

' (Da Capo, 1970 [1936]) * Schlebecker John T. ''Whereby we thrive: A history of American farming, 1607–1972'' (Iowa State UP, 1972) * Weeden, William Babcock.

Economic and Social History of New England, 1620–1789

' (Houghton, Mifflin, 1891)

"The Core Historical Literature of Agriculture"

from Cornell University Library {{History of biology History of agriculture, History of industries, Agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

began independently in different parts of the globe, and included a diverse range of taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

. At least eleven separate regions of the Old and New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

were involved as independent centers of origin

A center of origin is a geographical area where a group of organisms, either domesticated or wild, first developed its distinctive properties. They are also considered centers of diversity. Centers of origin were first identified in 1924 by Ni ...

.

The development of agriculture about 12,000 years ago changed the way humans lived. They switched from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to permanent settlements and farming.

Wild grains

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit (caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legumes ...

were collected and eaten from at least 105,000 years ago. However, domestication did not occur until much later. The earliest evidence of small-scale cultivation of edible grasses is from around 21,000 BC with the Ohalo II people on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. By around 9500 BC, the eight Neolithic founder crops

The founder crops (or primary domesticates) are the eight plant species that were domesticated by early Neolithic farming communities in Southwest Asia and went on to form the basis of agricultural economies across much of Eurasia, including Sout ...

– emmer wheat

Emmer wheat or hulled wheat is a type of awned wheat. Emmer is a tetraploid (4''n'' = 4''x'' = 28 chromosomes). The domesticated types are ''Triticum turgidum'' subsp. ''dicoccum'' and ''Triticum turgidum ''conv.'' durum''. The wild plant is ...

, einkorn wheat

Einkorn wheat (from German ''Einkorn'', literally "single grain") can refer either to a wild species of wheat (''Triticum'') or to its domesticated form. The wild form is '' T. boeoticum'' (syn. ''T. m.'' ssp. ''boeoticum''), the domesticated ...

, hulled barley, pea

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the flowering plant species ''Pisum sativum''. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and d ...

s, lentil

The lentil (''Lens culinaris'' or ''Lens esculenta'') is an edible legume. It is an annual plant known for its lens-shaped seeds. It is about tall, and the seeds grow in pods, usually with two seeds in each. As a food crop, the largest pro ...

s, bitter vetch Bitter vetch is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

* ''Vicia ervilia'', called bitter vetch or ervil, an ancient grain legume crop of the Mediterranean region.

*'' Vicia orobus'', called wood-bitter vetch, a legume found in Atlantic ...

, chickpeas, and flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

– were cultivated in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

. Rye may have been cultivated earlier, but this claim remains controversial. Rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown i ...

was domesticated in China by 6200 BC with earliest known cultivation from 5700 BC, followed by mung, soy

The soybean, soy bean, or soya bean (''Glycine max'') is a species of legume native to East Asia, widely grown for its edible bean, which has numerous uses.

Traditional unfermented food uses of soybeans include soy milk, from which tofu and ...

and azuki

''Vigna angularis'', also known as the adzuki bean , azuki bean, aduki bean, red bean, or red mung bean, is an annual vine widely cultivated throughout East Asia for its small (approximately long) bean. The cultivars most familiar in East As ...

beans. Rice was also independently domesticated in West Africa and cultivated by 1000 BC. Pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus ...

s were domesticated in Mesopotamia around 11,000 years ago, followed by sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus ''Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated s ...

. Cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult mal ...

were domesticated from the wild aurochs

The aurochs (''Bos primigenius'') ( or ) is an extinct cattle species, considered to be the wild ancestor of modern domestic cattle. With a shoulder height of up to in bulls and in cows, it was one of the largest herbivores in the Holocen ...

in the areas of modern Turkey and India around 8500 BC. Camels

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. ...

were domesticated late, perhaps around 3000 BC.

In subsaharan Africa, sorghum

''Sorghum'' () is a genus of about 25 species of flowering plants in the grass family (Poaceae). Some of these species are grown as cereals for human consumption and some in pastures for animals. One species is grown for grain, while many othe ...

was domesticated in the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid c ...

region of Africa by 3000 BC, along with pearl millet by 2000 BC. Yams were domesticated in several distinct locations, including West Africa (unknown date), and cowpea

The cowpea (''Vigna unguiculata'') is an annual herbaceous legume from the genus ''Vigna''. Its tolerance for sandy soil and low rainfall have made it an important crop in the semiarid regions across Africa and Asia. It requires very few inputs, ...

s by 2500 BC. Rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown i ...

(African rice

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown in West Africa around 3,000 years ago. In agriculture, it has largely been replaced by higher-yielding Asian ri ...

) was also independently domesticated in West Africa and cultivated by 1000 BC. Teff

''Eragrostis tef'', also known as teff, Williams lovegrass or annual bunch grass, is an annual grass, a species of lovegrass native to the Horn of Africa, notably to both Eritrea and Ethiopia. It is cultivated for its edible seeds, also known as ...

and likely finger millet

''Eleusine coracana'', or finger millet, also known as ragi in India, kodo in Nepal, is an annual herbaceous plant widely grown as a cereal crop in the arid and semiarid areas in Africa and Asia. It is a tetraploid and self-pollinating species p ...

were domesticated in Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

by 3000 BC, along with noog

''Guizotia abyssinica'' is an erect, stout, branched annual herb, grown for its edible oil and seed. Its cultivation originated in the Eritrean and Ethiopian highlands, and has spread to other parts of Ethiopia. Common names include noog/nug ( ...

, ensete

''Ensete'' is a genus of monocarpic flowering plants native to tropical regions of Africa and Asia. It is one of the three genera in the banana family, Musaceae, and includes the false banana or enset ('' E. ventricosum''), an economically impor ...

, and coffee

Coffee is a drink prepared from roasted coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulant, stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content. It is the most popular hot drink in the world.

S ...

. Other plant foods domesticated in Africa include watermelon

Watermelon (''Citrullus lanatus'') is a flowering plant species of the Cucurbitaceae family and the name of its edible fruit. A scrambling and trailing vine-like plant, it is a highly cultivated fruit worldwide, with more than 1,000 varieti ...

, okra

Okra or Okro (, ), ''Abelmoschus esculentus'', known in many English-speaking countries as ladies' fingers or ochro, is a flowering plant in the mallow family. It has edible green seed pods. The geographical origin of okra is disputed, with su ...

, tamarind

Tamarind (''Tamarindus indica'') is a Legume, leguminous tree bearing edible fruit that is probably indigenous to tropical Africa. The genus ''Tamarindus'' is monotypic taxon, monotypic, meaning that it contains only this species. It belongs ...

and black eyed peas, along with tree crops such as the kola nut and oil palm

''Elaeis'' () is a genus of palms containing two species, called oil palms. They are used in commercial agriculture in the production of palm oil. The African oil palm ''Elaeis guineensis'' (the species name ''guineensis'' referring to its co ...

. Plantains

Plantain may refer to:

Plants and fruits

* Cooking banana, banana cultivars in the genus ''Musa'' whose fruits are generally used in cooking

** True plantains, a group of cultivars of the genus ''Musa''

* ''Plantaginaceae'', a family of flowerin ...

were cultivated in Africa by 3000 BC and banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", distinguis ...

s by 1500 BC. The helmeted guineafowl

Guineafowl (; sometimes called "pet speckled hens" or "original fowl") are birds of the family Numididae in the order Galliformes. They are endemic to Africa and rank among the oldest of the gallinaceous birds. Phylogenetically, they branched ...

was domesticated in West Africa. Sanga cattle

Sanga cattle is the collective name for indigenous cattle of sub-Saharan Africa. They are sometimes identified as a subspecies with the scientific name ''Bos taurus africanus''. Their history of domestication and their origins in relation to t ...

was likely also domesticated in North-East Africa, around 7000 BC, and later crossbred with other species.

In South America, agriculture began as early as 9000 BC, starting with the cultivation of several species of plants that later became only minor crops. In the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

of South America, the potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Unit ...

was domesticated between 8000 BC and 5000 BC, along with beans

A bean is the seed of several plants in the family Fabaceae, which are used as vegetables for human or animal food. They can be cooked in many different ways, including boiling, frying, and baking, and are used in many traditional dishes th ...

, squash

Squash may refer to:

Sports

* Squash (sport), the high-speed racquet sport also known as squash racquets

* Squash (professional wrestling), an extremely one-sided match in professional wrestling

* Squash tennis, a game similar to squash but pla ...

, tomatoes

The tomato is the edible berry of the plant ''Solanum lycopersicum'', commonly known as the tomato plant. The species originated in western South America, Mexico, and Central America. The Mexican Nahuatl word gave rise to the Spanish word ...

, peanut

The peanut (''Arachis hypogaea''), also known as the groundnut, goober (US), pindar (US) or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible Seed, seeds. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics, important to both small ...

s, coca

Coca is any of the four cultivated plants in the family Erythroxylaceae, native to western South America. Coca is known worldwide for its psychoactive alkaloid, cocaine.

The plant is grown as a cash crop in the Argentine Northwest, Bolivia, ...

, llama

The llama (; ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a List of meat animals, meat and pack animal by Inca empire, Andean cultures since the Pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with othe ...

s, alpaca

The alpaca (''Lama pacos'') is a species of South American camelid mammal. It is similar to, and often confused with, the llama. However, alpacas are often noticeably smaller than llamas. The two animals are closely related and can successfu ...

s, and guinea pig

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy (), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus ''Cavia'' in the family Caviidae. Breeders tend to use the word ''cavy'' to describe the ani ...

s. Cassava

''Manihot esculenta'', common name, commonly called cassava (), manioc, or yuca (among numerous regional names), is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively ...

was domesticated in the Amazon Basin no later than 7000 BC. Maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

(''Zea mays'') found its way to South America from Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. W ...

, where wild teosinte

''Zea'' is a genus of flowering plants in the grass family. The best-known species is ''Z. mays'' (variously called maize, corn, or Indian corn), one of the most important crops for human societies throughout much of the world. The four wild sp ...

was domesticated about 7000 BC and selectively bred

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant m ...

to become domestic maize. Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

was domesticated in Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

by 4200 BC; another species of cotton was domesticated in Mesoamerica and became by far the most important species of cotton in the textile industry in modern times. Evidence of agriculture in the Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

United States dates to about 3000 BCE. Several plants were cultivated, later to be replaced by the Three Sisters cultivation of maize, squash, and beans.

Sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with ...

and some root vegetables

Root vegetables are underground plant parts eaten by humans as food. Although botany distinguishes true roots (such as taproots and tuberous roots) from non-roots (such as bulbs, corms, rhizomes, and tubers, although some contain both hypocotyl ...

were domesticated in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

around 7000 BC. Banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", distinguis ...

s were cultivated and hybridized in the same period in Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

. In Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, agriculture was invented at a currently unspecified period, with the oldest eel traps of Budj Bim dating to 6,600 BC and the deployment of several crops ranging from yamsGammage, Bill (October 2011). The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin. pp. 281–304. . to bananas.

The Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, from c. 3300 BC, witnessed the intensification of agriculture in civilizations such as Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

n Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of c ...

, ancient Egypt, ancient Sudan, the Indus Valley civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

of the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

, ancient China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapte ...

, and ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

. From 100 BC to 1600 AD, world population continued to grow along with land use, as evidenced by the rapid increase in methane emissions

Increasing methane emissions are a major contributor to the rising concentration of greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere, and are responsible for up to one-third of near-term global heating. During 2019, about 60% (360 million tons) of methane r ...

from cattle and the cultivation of rice. During the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

and era of classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, the expansion of ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 B ...

, both the Republic and then the Empire, throughout the ancient Mediterranean

The history of the Mediterranean region and of the cultures and people of the Mediterranean Basin is important for understanding the origin and development of the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Canaanite, Phoenician, Hebrew, Carthaginian, Minoan, Gre ...

and Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

built upon existing systems of agriculture while also establishing the manorial

Manorialism, also known as the manor system or manorial system, was the method of land ownership (or "tenure") in parts of Europe, notably France and later England, during the Middle Ages. Its defining features included a large, sometimes forti ...

system that became a bedrock of medieval agriculture. In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, both in Europe and in the Islamic world, agriculture was transformed with improved techniques and the diffusion of crop plants, including the introduction of sugar, rice, cotton and fruit trees such as the orange

Orange most often refers to:

*Orange (fruit), the fruit of the tree species '' Citrus'' × ''sinensis''

** Orange blossom, its fragrant flower

*Orange (colour), from the color of an orange, occurs between red and yellow in the visible spectrum

* ...

to Europe by way of Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

. After the voyages of Christopher Columbus

Between 1492 and 1504, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus led four Spanish transatlantic maritime expeditions of discovery to the Americas. These voyages led to the widespread knowledge of the New World. This breakthrough inaugurated the per ...

in 1492, the Columbian exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World (the Americas) in ...

brought New World crops such as maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

, potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Unit ...

es, tomato

The tomato is the edible berry of the plant ''Solanum lycopersicum'', commonly known as the tomato plant. The species originated in western South America, Mexico, and Central America. The Mexican Nahuatl word gave rise to the Spanish word ...

es, sweet potato

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (''Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the Convolvulus, bindweed or morning glory family (biology), family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a r ...

es, and manioc

''Manihot esculenta'', commonly called cassava (), manioc, or yuca (among numerous regional names), is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively cultivated a ...

to Europe, and Old World crops such as wheat, barley, rice, and turnip

The turnip or white turnip ('' Brassica rapa'' subsp. ''rapa'') is a root vegetable commonly grown in temperate climates worldwide for its white, fleshy taproot. The word ''turnip'' is a compound of ''turn'' as in turned/rounded on a lathe and ...

s, and livestock including horses, cattle, sheep, and goats to the Americas.

Irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

, crop rotation

Crop rotation is the practice of growing a series of different types of crops in the same area across a sequence of growing seasons. It reduces reliance on one set of nutrients, pest and weed pressure, and the probability of developing resistant ...

, and fertilizer

A fertilizer (American English) or fertiliser (British English; see spelling differences) is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from ...

s were introduced soon after the Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, or the (First) Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an incre ...

and developed much further in the past 200 years, starting with the British Agricultural Revolution

The British Agricultural Revolution, or Second Agricultural Revolution, was an unprecedented increase in agricultural production in Britain arising from increases in labour and land productivity between the mid-17th and late 19th centuries. Agric ...

. Since 1900, agriculture in the developed nations, and to a lesser extent in the developing world, has seen large rises in productivity as human labour has been replaced by mechanization

Mechanization is the process of changing from working largely or exclusively by hand or with animals to doing that work with machinery. In an early engineering text a machine is defined as follows:

In some fields, mechanization includes the ...

, and assisted by synthetic fertilizers, pesticide

Pesticides are substances that are meant to control pests. This includes herbicide, insecticide, nematicide, molluscicide, piscicide, avicide, rodenticide, bactericide, insect repellent, animal repellent, microbicide, fungicide, and lampri ...

s, and selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant mal ...

. The Haber-Bosch process

The Haber process, also called the Haber–Bosch process, is an artificial nitrogen fixation process and is the main industrial procedure for the production of ammonia today. It is named after its inventors, the German chemists Fritz Haber and C ...

allowed the synthesis of ammonium nitrate

Ammonium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a white crystalline salt consisting of ions of ammonium and nitrate. It is highly soluble in water and hygroscopic as a solid, although it does not form hydrates. It is ...

fertilizer on an industrial scale, greatly increasing crop yields

In agriculture, the yield is a measurement of the amount of a crop grown, or product such as wool, meat or milk produced, per unit area of land. The seed ratio is another way of calculating yields.

Innovations, such as the use of fertilizer, the c ...

. Modern agriculture has raised social, political, and environmental issues including overpopulation, water pollution

Water pollution (or aquatic pollution) is the contamination of water bodies, usually as a result of human activities, so that it negatively affects its uses. Water bodies include lakes, rivers, oceans, aquifers, reservoirs and groundwater. Water ...

, biofuel

Biofuel is a fuel that is produced over a short time span from biomass, rather than by the very slow natural processes involved in the formation of fossil fuels, such as oil. According to the United States Energy Information Administration (E ...

s, genetically modified organism

A genetically modified organism (GMO) is any organism whose genetic material has been altered using genetic engineering techniques. The exact definition of a genetically modified organism and what constitutes genetic engineering varies, with ...

s, tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s and farm subsidies

An agricultural subsidy (also called an agricultural incentive) is a government incentive paid to agribusinesses, agricultural organizations and farms to supplement their income, manage the supply of agricultural commodities, and influence t ...

. In response, organic farming

Organic farming, also known as ecological farming or biological farming,Labelling, article 30 o''Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on organic production and labelling of organic products and re ...

developed in the twentieth century as an alternative to the use of synthetic pesticides.

Origins

Origin hypotheses

Scholars have developed a number of hypotheses to explain the historical origins of agriculture. Studies of the transition fromhunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

to agricultural societies indicate an antecedent period of intensification and increasing sedentism

In cultural anthropology, sedentism (sometimes called sedentariness; compare sedentarism) is the practice of living in one place for a long time. , the large majority of people belong to sedentary cultures. In evolutionary anthropology and a ...

; examples are the Natufian culture

The Natufian culture () is a Late Epipaleolithic archaeological culture of the Levant, dating to around 15,000 to 11,500 years ago. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentary or semi-sedentary population even before the introduction ...

in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, and the Early Chinese Neolithic in China. Current models indicate that wild stands that had been harvested previously started to be planted, but were not immediately domesticated.

Localised climate change is the favoured explanation for the origins of agriculture in the Levant. When major climate change took place after the last ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

(c. 11,000 BC), much of the earth became subject to long dry seasons. These conditions favoured annual plant

An annual plant is a plant that completes its life cycle, from germination to the production of seeds, within one growing season, and then dies. The length of growing seasons and period in which they take place vary according to geographical ...

s which die off in the long dry season, leaving a dormant seed

A seed is an embryonic plant enclosed in a protective outer covering, along with a food reserve. The formation of the seed is a part of the process of reproduction in seed plants, the spermatophytes, including the gymnosperm and angiospe ...

or tuber

Tubers are a type of enlarged structure used as storage organs for nutrients in some plants. They are used for the plant's perennation (survival of the winter or dry months), to provide energy and nutrients for regrowth during the next growin ...

. An abundance of readily storable wild grains and pulses

In medicine, a pulse represents the tactile arterial palpation of the cardiac cycle (heartbeat) by trained fingertips. The pulse may be palpated in any place that allows an artery to be compressed near the surface of the body, such as at the nec ...

enabled hunter-gatherers in some areas to form the first settled villages at this time.

Early development

Early people began altering communities of

Early people began altering communities of flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

E ...

and fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zoo ...

for their own benefit through means such as fire-stick farming and forest gardening

Forest gardening is a low-maintenance, Sustainable gardening, sustainable, plant-based food production and agroforestry system based on woodland ecosystems, incorporating fruit and Nut (fruit), nut trees, shrubs, herbs, vines and perennial vegeta ...

very early.

Wild grains

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit (caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legumes ...

have been collected and eaten from at least 105,000 years ago, and possibly much longer. Exact dates are hard to determine, as people collected and ate seeds before domesticating them, and plant characteristics may have changed during this period without human selection. An example is the semi-tough rachis

In biology, a rachis (from the grc, ῥάχις [], "backbone, spine") is a main axis or "shaft".

In zoology and microbiology

In vertebrates, ''rachis'' can refer to the series of articulated vertebrae, which encase the spinal cord. In this c ...

and larger seeds of cereal

A cereal is any Poaceae, grass cultivated for the edible components of its grain (botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, Cereal germ, germ, and bran. Cereal Grain, grain crops are grown in greater quantit ...

s from just after the Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas (c. 12,900 to 11,700 years BP) was a return to glacial conditions which temporarily reversed the gradual climatic warming after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, c. 27,000 to 20,000 years BP). The Younger Dryas was the last stage ...

(about 9500 BC) in the early Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togethe ...

in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

region of the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent ( ar, الهلال الخصيب) is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Jordan, together with the northern region of Kuwait, southeastern region of ...

. Monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gro ...

characteristics were attained without any human intervention, implying that apparent domestication of the cereal rachis

In biology, a rachis (from the grc, ῥάχις [], "backbone, spine") is a main axis or "shaft".

In zoology and microbiology

In vertebrates, ''rachis'' can refer to the series of articulated vertebrae, which encase the spinal cord. In this c ...

could have occurred quite naturally.

Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe and included a diverse range of taxa. At least 11 separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent

Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe and included a diverse range of taxa. At least 11 separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent centers of origin

A center of origin is a geographical area where a group of organisms, either domesticated or wild, first developed its distinctive properties. They are also considered centers of diversity. Centers of origin were first identified in 1924 by Ni ...

. Some of the earliest known domestications were of animals. Domestic pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus s ...

s had multiple centres of origin in Eurasia, including Europe, East Asia and Southwest Asia, where wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The species is ...

were first domesticated about 10,500 years ago. Sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus ''Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated s ...

were domesticated in Mesopotamia between 11,000 BC and 9000 BC. Cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult mal ...

were domesticated from the wild aurochs

The aurochs (''Bos primigenius'') ( or ) is an extinct cattle species, considered to be the wild ancestor of modern domestic cattle. With a shoulder height of up to in bulls and in cows, it was one of the largest herbivores in the Holocen ...

in the areas of modern Turkey and Pakistan around 8500 BC. Camels

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. ...

were domesticated late, perhaps around 3000 BC.

It was not until after 9500 BC that the eight so-called founder crops of agriculture appear: first

It was not until after 9500 BC that the eight so-called founder crops of agriculture appear: first emmer

Emmer wheat or hulled wheat is a type of awned wheat. Emmer is a tetraploid (4''n'' = 4''x'' = 28 chromosomes). The domesticated types are ''Triticum turgidum'' subsp. ''dicoccum'' and ''Triticum turgidum ''conv.'' durum''. The wild plant is ...

and einkorn wheat

Einkorn wheat (from German ''Einkorn'', literally "single grain") can refer either to a wild species of wheat (''Triticum'') or to its domesticated form. The wild form is '' T. boeoticum'' (syn. ''T. m.'' ssp. ''boeoticum''), the domesticated ...

, then hulled barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley pr ...

, pea

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the flowering plant species ''Pisum sativum''. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and d ...

s, lentil

The lentil (''Lens culinaris'' or ''Lens esculenta'') is an edible legume. It is an annual plant known for its lens-shaped seeds. It is about tall, and the seeds grow in pods, usually with two seeds in each. As a food crop, the largest pro ...

s, bitter vetch Bitter vetch is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

* ''Vicia ervilia'', called bitter vetch or ervil, an ancient grain legume crop of the Mediterranean region.

*'' Vicia orobus'', called wood-bitter vetch, a legume found in Atlantic ...

, chick pea

The chickpea or chick pea (''Cicer arietinum'') is an annual legume of the family Fabaceae, subfamily Faboideae. Its different types are variously known as gram" or Bengal gram, garbanzo or garbanzo bean, or Egyptian pea. Chickpea seeds are hi ...

s and flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

. These eight crops occur more or less simultaneously on Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to years ago, that is, 8800–6500 BC. It was typed by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon duri ...

) sites in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, although wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

was the first to be grown and harvested on a significant scale. At around the same time (9400 BC), parthenocarpic

In botany and horticulture, parthenocarpy is the natural or artificially induced production of fruit without fertilisation of ovules, which makes the fruit seedless. Stenospermocarpy may also produce apparently seedless fruit, but the seeds are ac ...

fig

The fig is the edible fruit of ''Ficus carica'', a species of small tree in the flowering plant family Moraceae. Native to the Mediterranean and western Asia, it has been cultivated since ancient times and is now widely grown throughout the world ...

trees were domesticated.

Domesticated rye occurs in small quantities at some Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

sites in (Asia Minor) Turkey, such as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to years ago, that is, 8800–6500 BC. It was typed by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon during h ...

(c. 7600 – c. 6000 BC) Can Hasan III near Çatalhöyük

Çatalhöyük (; also ''Çatal Höyük'' and ''Çatal Hüyük''; from Turkish ''çatal'' "fork" + ''höyük'' "tumulus") is a tell of a very large Neolithic and Chalcolithic proto-city settlement in southern Anatolia, which existed from app ...

, but is otherwise absent until the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

of central Europe, c. 1800–1500 BC. Claims of much earlier cultivation of rye, at the Epipalaeolithic

In archaeology, the Epipalaeolithic or Epipaleolithic (sometimes Epi-paleolithic etc.) is a period occurring between the Upper Paleolithic and Neolithic during the Stone Age. Mesolithic also falls between these two periods, and the two are someti ...

site of Tell Abu Hureyra

Tell Abu Hureyra ( ar, تل أبو هريرة) is a prehistoric archaeological site in the Upper Euphrates valley in Syria. The tell was inhabited between 13,000 and 9,000 years ago in two main phases: Abu Hureyra 1, dated to the Epipalaeolithi ...

in the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

valley of northern Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, remain controversial. Critics point to inconsistencies in the radiocarbon

Carbon-14, C-14, or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with an atomic nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic materials is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and coll ...

dates, and identifications based solely on grain, rather than on chaff

Chaff (; ) is the dry, scaly protective casing of the seeds of cereal grains or similar fine, dry, scaly plant material (such as scaly parts of flowers or finely chopped straw). Chaff is indigestible by humans, but livestock can eat it. In agri ...

.

By 8000 BC, farming was entrenched on the banks of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

. About this time, agriculture was developed independently in the Far East, probably in China, with rice rather than wheat as the primary crop. Maize was domesticated from the wild grass teosinte

''Zea'' is a genus of flowering plants in the grass family. The best-known species is ''Z. mays'' (variously called maize, corn, or Indian corn), one of the most important crops for human societies throughout much of the world. The four wild sp ...

in southern Mexico by 6700 BC.

The potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Unit ...

(8000 BC), tomato

The tomato is the edible berry of the plant ''Solanum lycopersicum'', commonly known as the tomato plant. The species originated in western South America, Mexico, and Central America. The Mexican Nahuatl word gave rise to the Spanish word ...

, pepper

Pepper or peppers may refer to:

Food and spice

* Piperaceae or the pepper family, a large family of flowering plant

** Black pepper

* ''Capsicum'' or pepper, a genus of flowering plants in the nightshade family Solanaceae

** Bell pepper

** Chili ...

(4000 BC), squash

Squash may refer to:

Sports

* Squash (sport), the high-speed racquet sport also known as squash racquets

* Squash (professional wrestling), an extremely one-sided match in professional wrestling

* Squash tennis, a game similar to squash but pla ...

(8000 BC) and several varieties of bean

A bean is the seed of several plants in the family Fabaceae, which are used as vegetables for human or animal food. They can be cooked in many different ways, including boiling, frying, and baking, and are used in many traditional dishes th ...

(8000 BC onwards) were domesticated in the New World.

Agriculture was independently developed on the island of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

. Banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", distinguis ...

cultivation of ''Musa acuminata

''Musa acuminata'' is a species of banana native to South Asia, Southern Asia, its range comprising the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Many of the modern edible dessert bananas are from this species, although some are hybrids with ''Mus ...

'', including hybridization, dates back to 5000 BC, and possibly to 8000 BC, in Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

.

Bees were kept for honey in the Middle East around 7000 BC. Archaeological evidence from various sites on the Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

suggest the domestication of plants and animals between 6000 and 4500 BC. Céide Fields

The Céide Fields () is an archaeological site on the north County Mayo coast in the west of Ireland, about northwest of Ballycastle. The site has been described as the most extensive Neolithic site in Ireland and is claimed to contain the old ...

in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, consisting of extensive tracts of land enclosed by stone walls, date to 3500 BC and are the oldest known field systems in the world. The horse was domesticated in the Pontic steppe

Pontic, from the Greek ''pontos'' (, ), or "sea", may refer to:

The Black Sea Places

* The Pontic colonies, on its northern shores

* Pontus (region), a region on its southern shores

* The Pontic–Caspian steppe, steppelands stretching from no ...

around 4000 BC. In Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

, Cannabis

''Cannabis'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae. The number of species within the genus is disputed. Three species may be recognized: ''Cannabis sativa'', '' C. indica'', and '' C. ruderalis''. Alternatively ...

was in use in China in Neolithic times and may have been domesticated there; it was in use both as a fibre for ropemaking and as a medicine in Ancient Egypt by about 2350 BC.

In northern

In northern China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets al ...

was domesticated by early Sino-Tibetan

Sino-Tibetan, also cited as Trans-Himalayan in a few sources, is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Chinese languages. ...

speakers at around 8000 to 6000 BC, becoming the main crop of the Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Standard Beijing Mandarin, Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the List of rivers by length, sixth-longest river system in the world at th ...

basin by 5500 BC. They were followed by mung, soy

The soybean, soy bean, or soya bean (''Glycine max'') is a species of legume native to East Asia, widely grown for its edible bean, which has numerous uses.

Traditional unfermented food uses of soybeans include soy milk, from which tofu and ...

and azuki

''Vigna angularis'', also known as the adzuki bean , azuki bean, aduki bean, red bean, or red mung bean, is an annual vine widely cultivated throughout East Asia for its small (approximately long) bean. The cultivars most familiar in East As ...

beans.

Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest list of rivers of Asia, river in Asia, the list of rivers by length, third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in th ...

basin at around 11,500 to 6200 BC, along with the development of wetland agriculture

A paddy field is a flooded field of arable land used for growing semiaquatic crops, most notably rice and taro. It originates from the Neolithic rice-farming cultures of the Yangtze River basin in southern China, associated with pre-Aust ...

, by early Austronesian and Hmong-Mien-speakers. Other food plants were also harvested, including acorn

The acorn, or oaknut, is the nut of the oaks and their close relatives (genera ''Quercus'' and '' Lithocarpus'', in the family Fagaceae). It usually contains one seed (occasionally

two seeds), enclosed in a tough, leathery shell, and borne ...

s, water chestnuts Water chestnut may refer to either of two plants (both sometimes used in Chinese cuisine):

* The Chinese water chestnut ('' Eleocharis dulcis''), eaten for its crisp corm

* The water caltrop

The water caltrop is any of three extant species of th ...

, and foxnut

''Euryale ferox,'' commonly known as prickly waterlily, makhana or Gorgon plant, is a species of water lily found in southern and eastern Asia, and the only extant member of the genus ''Euryale''. The edible seeds, called fox nuts or ''makhan ...

s. Rice cultivation was later spread to Island Southeast Asia by the Austronesian expansion

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Austron ...

, starting at around 3,500 to 2,000 BC. This migration event also saw the introduction of cultivated and domesticated food plants from Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

, Island Southeast Asia, and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

into the Pacific Islands

Collectively called the Pacific Islands, the islands in the Pacific Ocean are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of se ...

as canoe plants

One of the major human migration events was the maritime settlement of the islands of the Indo-Pacific by the Austronesian peoples, believed to have started from at least 5,500 to 4,000 BP (3500 to 2000 BCE). These migrations were accompani ...

. Contact with Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and Southern India